You Didn’t Fall Because You Tripped - You Fell Because You Didn’t Recover

I ran a trail race recently. Thirteen miles on hard-packed dirt, roots and rocks scattered across the path like nature’s obstacle course. Our group averaged around 62 years old. Five of us, all in decent shape, all capable of covering the distance.

One of us was a particularly skilled distance runner who logs serious weekly mileage, has been at this for decades, and knows how to pace, breathe, and suffer efficiently.

He fell three times. The roots got him. Each time his foot caught, he went down hard.

The rest of us caught our feet, too. It’s inevitable on a trail like that. But we didn’t fall.

What made the difference wasn’t fitness. It wasn’t strength. It wasn’t even his experience as a runner.

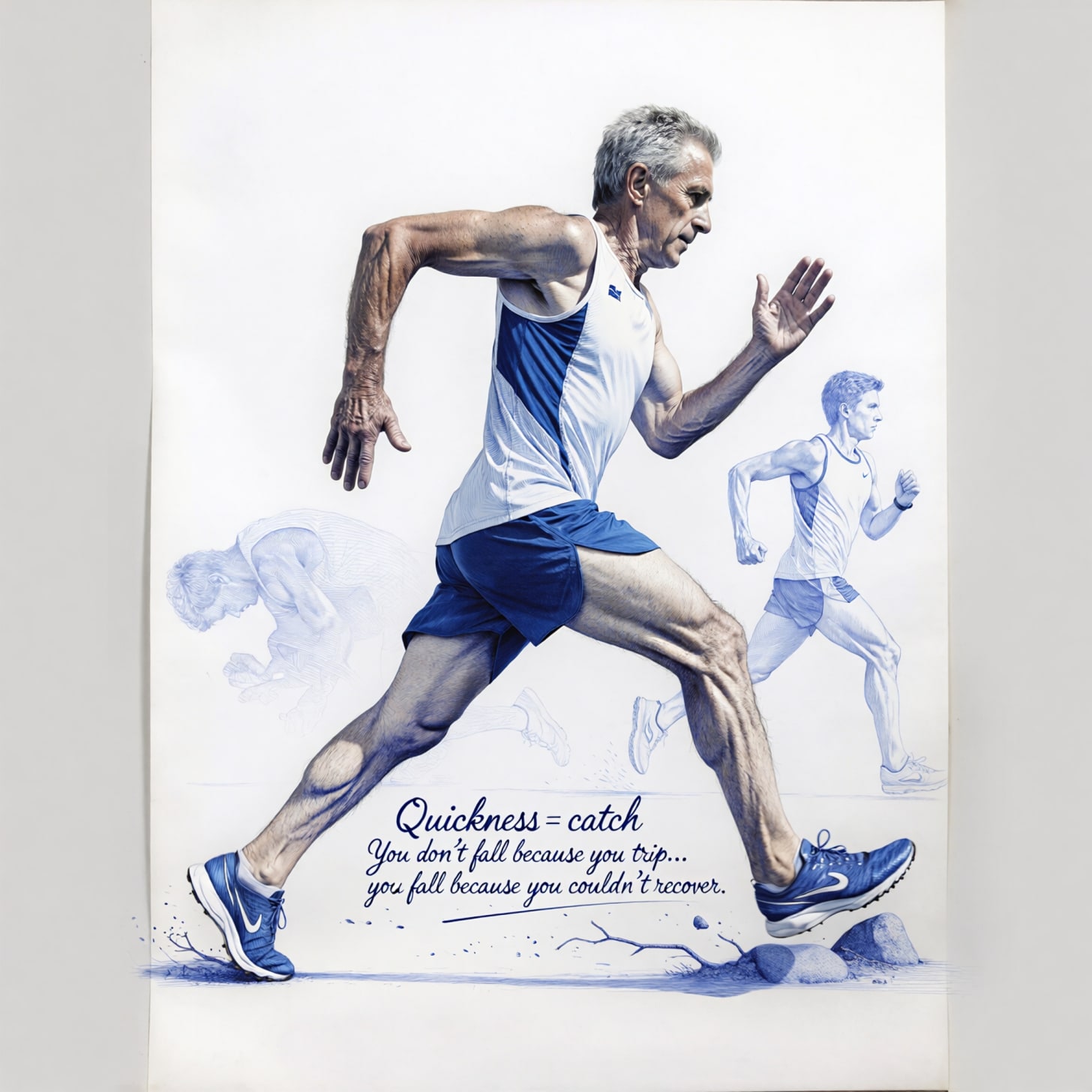

It was the loss of power and quickness - the ability to recover from a trip before it becomes a fall. I recognized the deficiency easily from my position behind him. The trip, and no attempt at recovery.

He wasn’t injured badly during these falls. A few cuts and scrapes, as well as a damaged ego… but that’s not the issue. Falls are a leading cause of death and disability. This puts his future health at risk. Let’s explore this further.

The Difference Between Tripping and Falling

Everyone trips. Your foot catches a root, a rock shifts under your step, your toe drags just slightly on uneven ground. This happens to everyone who moves through the world, especially on trails or uneven surfaces.

But not everyone falls.

Falling happens when you can’t recover from the trip. When your foot gets caught, and your body keeps moving forward, you have a fraction of a second to respond. You need to get your other leg out in front of you - fast (quickness). And once it’s there, you need to be able to generate enough force to stop your forward momentum and stabilize (power).

If you have both, you stumble and catch yourself… most of the time. If you don’t, you go down.

The two strength coaches I work with at Apollo Performance Training have been drilling this into me for years. Nearly every time, we have both quickness and power moves incorporated into my training day. Squats alone won’t do it.

What We Lose First as We Age

Aging doesn’t strip away all physical qualities equally. We lose some things faster than others.

Muscle mass declines gradually - sarcopenia begins around age 30 and accelerates after 50, but it’s a slow process. You lose roughly 3-8% per decade after 30 if you’re inactive, less if you’re training.

Absolute strength declines, too, but it’s also relatively slow if you’re lifting regularly. Many people in their 60s and 70s can maintain impressive levels of strength with consistent resistance training.

But power and quickness? Those skills drop off a cliff.

Power - the ability to generate force rapidly - starts declining earlier and faster than strength. Peak power output drops about 10% per decade after age 30, and the decline accelerates after 50. By 70, many people have lost 30-40% of their peak power even if they’ve maintained decent strength levels.

Quickness - the speed of muscle contraction and limb movement - declines even faster. Fast-twitch muscle fibers atrophy more rapidly than slow-twitch fibers. Nerve conduction velocity slows. The time it takes to react and move decreases.

This is why older adults can still deadlift heavy weights (pure strength) but struggle to catch themselves when they trip (power and speed). The systems required for explosive, rapid movement degrade faster than the systems required for sustained, controlled force production.

Why My Running Buddy Fell

My friend, who fell three times, is a skilled runner. He has excellent aerobic fitness. His legs are strong enough to carry him through long trail runs. He trains consistently.

But distance running doesn’t train power or quickness. It trains endurance - the ability to produce moderate force repeatedly over long periods. That’s a different quality.

When his foot caught those roots, he needed to explosively move his other leg forward and plant it forcefully to arrest his momentum. It requires fast-twitch muscle fibers firing rapidly, explosive hip flexion, and quick ground contact time.

He didn’t have it. But… not because he’s unfit, but because distance running alone doesn’t develop those qualities. If anything, excessive endurance training without power work can further bias the body toward slow-twitch muscle dominance. This sets the stage for significant potential issues as we age.

The rest of us - some of whom do plyometrics, some who lift explosively, some who train agility or play sports requiring quick changes of direction - had enough residual power and quickness to recover from the trips.

Not because we’re better runners. Because we’d maintained the physical qualities that prevent falls.

The Fall Prevention Paradox

Most fall prevention programs focus on balance and strength. Standing on one leg. Sit-to-stand exercises. Resistance training with slow, controlled movements. These help. Balance matters. Strength matters. But they’re not sufficient.

The strongest predictor of falls isn’t weak muscles or poor balance. It’s impaired reactive recovery - the inability to respond quickly and forcefully when stability is threatened.

You don’t fall because you’re weak. You fall because you’re slow.

When a young person trips, their nervous system detects the perturbation in milliseconds, activates muscles explosively, and repositions limbs fast enough to recover. The entire sequence happens in a fraction of a second.

When an older person trips, that sequence takes longer. Detection is slower. Muscle activation is delayed. Force production is blunted. Limb repositioning isn’t fast enough. Therefore, the trip becomes a fall.

What Actually Prevents Falls- Power Training Programming

If power and quickness are what allow you to recover from a trip, then fall prevention requires training those qualities.

Not just strength. Not just balance, but power and speed.

Power training means: (I’ve demonstrated many of these in my Saturday Morning Action Plan posts over the last few months).

Medicine ball throws (explosive upper body and rotational power)

Box step-ups at tempo (explosive leg drive)

Kettlebell swings (hip power)

Jump training - even low-level plyometrics like step-downs, small box jumps, or jumping off a curb

Olympic lift variations if you’re trained (cleans, snatches, high pulls)

Speed squats or speed deadlifts (lifting moderate weight as explosively as possible)

Quickness training means:

Agility drills (ladder drills, cone drills, direction changes)

Reactive stepping exercises (stepping quickly in response to a cue)

Sport-specific movements that require rapid responses (tennis, pickleball, basketball)

Balance perturbation training (standing on unstable surfaces and recovering quickly when pushed off balance)

The key difference: these aren’t slow, controlled movements. They’re fast, explosive, and reactive.

You’re training your nervous system to fire quickly and your muscles to produce force rapidly. That’s what saves you when you trip on a root.

The Evidence

Studies on fall prevention show that leg muscle power is more predictive of falls than strength. In one study of community-dwelling older adults, no significant differences were found between fallers and non-fallers in knee extensor or flexor strength. But, non-fallers demonstrated significantly greater leg muscle power than fallers [1].

A systematic review and meta-analysis found that power training improves functional capacity related to fall risk more than other forms of exercise in older adults, with improvements in both the timed up-and-go test and the 30-second sit-to-stand test [2].

A comprehensive systematic review with meta-analysis showed that lower average leg-press power and lower peak sit-to-stand power predict prospective falls in older adults. The decline in lower-limb power appears to be a particularly good indicator of prospective falls, especially injurious and recurrent falls [3].

An updated meta-analysis of 54 randomized controlled trials confirms that exercise, as a single intervention, can prevent falls in community-dwelling older people, with programs that challenge balance and include higher doses of exercise showing larger effects [4].

Power and quickness are trainable well into old age. But you actually have to train them. Doing slow squats and bicep curls won’t cut it.

The Practical Challenge

Most people over 50 aren’t doing any power training. Their exercise routine consists of walking, maybe some slow resistance training, maybe yoga or stretching. As I have discussed often, many people fear training explosive moves due to the perceived injury risk. But the risk of serious injury due to a fall is higher than the risk of injury while training under a professional’s care. Many older adults avoid explosive movements out of fear of injury. Jumping feels risky. Moving fast feels dangerous. So they slow everything down, which ironically makes them more fragile.

The safe approach isn’t avoiding explosive movement. It’s progressing intelligently toward it.

Start with:

Step-downs from a low step (control the descent, then step up quickly)

Medicine ball chest passes against a wall (light ball, focus on speed)

Quick feet drills (standing in place, lifting knees rapidly for 10 seconds)

Reactive stepping (partner calls out a direction, you step that way quickly)

Progress to:

Small box jumps (6-12 inches)

Kettlebell swings

Rotational throws

Lateral hops

Agility ladder work

Two sessions per week, 10-15 minutes each, are enough to maintain power and quickness. You’re not training to be an athlete. You’re training so that when your foot catches a root, your body responds fast enough to keep you upright.

Why This Matters

Falls are one of the leading causes of injury, hospitalization, and loss of independence in older adults.

One in four adults over 65 falls each year. Of those who fall and break a hip, 20-30% die within a year. Of those who survive, many never regain full independence.

Most falls don't happen because someone is frail; they happen because they couldn’t recover from a trip. Their nervous system and muscles weren’t fast enough to respond.

This is preventable. Power and quickness are trainable. But they require intentional work. They don’t come from walking more or doing slow resistance training.

You need to train fast to stay fast.

My running partner is fit. He’s strong. He has excellent endurance. But he fell three times on that trail because he lacked the power and quickness to recover when his foot caught.

Those qualities don’t stick around just because you stay active. They decline faster than almost anything else as we age.

If you want to stay upright - on trails, on stairs, on icy sidewalks, in your kitchen when you slip on a wet floor - you need to train power and speed.

Not occasionally, but regularly, and intentionally.

Start training now, please, before the next root finds you.

-Howard

References:

[1] Simpkins C, Yang F. Muscle power is more important than strength in preventing falls in community-dwelling older adults. Journal of Biomechanics. 2022;134:111018.

[2] Fernández-Gavira J, Huerta-Ojeda Á, Chirosa-Ríos LJ. Effects of Power Training on Functional Capacity Related to Fall Risk in Older Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2023;104(7):1091-1104.

[3] Zhang L, Li Y, Yue L, et al. Association of lower-limb strength with different fall histories or prospective falls in community-dwelling older people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Geriatrics. 2025;25(1):77.

[4] Sherrington C, Michaleff ZA, Fairhall N, et al. Exercise to prevent falls in older adults: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2017;51(24):1750-1758.

Popular Products

-

Classic Oversized Teddy Bear

Classic Oversized Teddy Bear$23.78 -

Gem's Ballet Natural Garnet Gemstone ...

Gem's Ballet Natural Garnet Gemstone ...$171.56$85.78 -

Butt Lifting Body Shaper Shorts

Butt Lifting Body Shaper Shorts$95.56$47.78 -

Slimming Waist Trainer & Thigh Trimmer

Slimming Waist Trainer & Thigh Trimmer$67.56$33.78 -

Realistic Fake Poop Prank Toys

Realistic Fake Poop Prank Toys$99.56$49.78