Americans Now Have Much More Money In Iras Than 401(k)s. Why That Leaves Workers More Vulnerable.

With fewer protections and guardrails, we have a much less effective system.

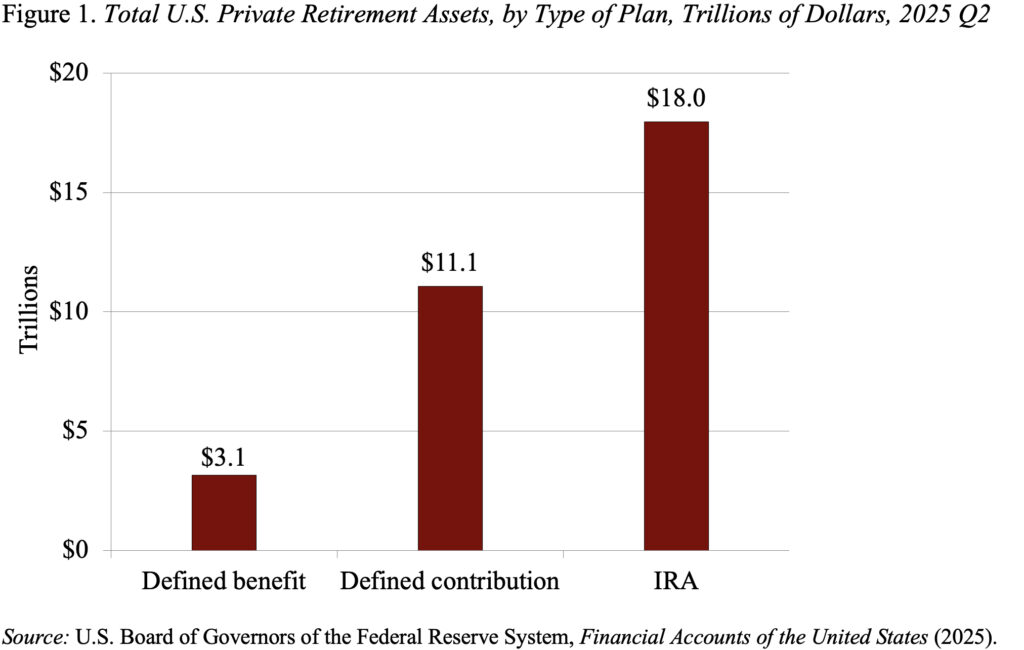

The most extraordinary development in the U.S. private sector retirement system is not the shift away from old-fashioned defined benefit plans, which began around 1980 and is virtually complete today, but rather the movement away from 401(k) plans, which replaced the defined benefit plans, to Individual Retirement Accounts (IRAs). Total IRA assets now exceed the money in 401(k)s by $7 trillion (see Figure 1).

The shift from 401(k)s to IRAs moves the employees’ money to a different regulatory environment. 401(k) plans are covered by the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974 (ERISA), which requires plan sponsors to operate as fiduciaries who always act in the best interest of plan participants. In contrast, the standards of conduct for broker-dealers selling IRA investments are much less protective than the ERISA fiduciary duties of loyalty and prudence, which have consistently been characterized by the courts as “the highest known to the law.” In addition, in the 401(k) environment, much greater emphasis is placed on the disclosure of fees in an understandable format than in the case of IRAs. And, most importantly, 401(k)s place much more emphasis than IRAs on keeping the funds in the plan until retirement.

Virtually all withdrawals from 401(k) plans and traditional IRAs made before the employee reaches age 59½ are subject to a 10-percent penalty tax (in addition to federal and state income taxes). Exceptions include distributions for large healthcare expenses, for hardship caused by permanent and total disability, and for periodic payments over a lifetime. IRAs, however, offer withdrawals for three additional reasons: to cover postsecondary education expenses; up to $10,000 to cover a new home purchase; and to pay medical insurance expenses for those unemployed for 12 or more weeks.

In addition to the exemptions from the 10-percent penalty tax, the barriers to accessing funds are much lower in the case of IRAs than 401(k)s. Importantly, 401(k) withdrawals can be made only at job change or for reasons of hardship, while IRA withdrawals can be made at any time and without justification. Moreover, 401(k) hardship withdrawals involve interactions with plan administrators, the filing of paperwork, and, at least in theory, a justification for the withdrawal. The emotional and practical burden of this multi-stage process may discourage withdrawals. In contrast, the providers of IRAs generally do not discourage withdrawals prior to reaching retirement age. And finally, while in 1992 Congress imposed a 20-percent withholding on monies taken out of a 401(k), no such withholding exists on IRA transactions.

The growing role of IRAs has resulted in a much less effective retirement system. Without fiduciaries serving as a buffer between the participant and the market, investments will be suboptimal. With many more options for withdrawing money from accounts, leakages will increase. In addition, IRAs offer less protection than 401(k)s. They protect fewer assets in the event of bankruptcy or litigation and offer less assurance for spouses – the 401(k) designates the spouse as the default beneficiary, requiring notarized consent to name someone else, while IRAs allow the owner to name any beneficiary.

The bottom line is this. Wise people used to think that ERISA was cool because it protected the benefits of participants in workplace retirement plans. Even those who agree that its administrative burden and costs may have contributed to the demise of defined-benefit plans still laud its protections. Shouldn’t we care that only 45 percent of assets in the private sector are protected by ERISA? And what should we do about it?

Popular Products

-

Put Me Down Funny Toilet Seat Sticker

Put Me Down Funny Toilet Seat Sticker$33.56$16.78 -

Stainless Steel Tongue Scrapers

Stainless Steel Tongue Scrapers$33.56$16.78 -

Stylish Blue Light Blocking Glasses

Stylish Blue Light Blocking Glasses$85.56$42.78 -

Adjustable Ankle Tension Rope

Adjustable Ankle Tension Rope$53.56$26.78 -

Electronic Bidet Toilet Seat

Electronic Bidet Toilet Seat$981.56$490.78